The Crypt

The Falcon's Children, Chapter 21

From the infirmary she could hear her sisters singing.

The room was not large but compared to the sleeping cells it was palatial: Six beds, as many tables, and then a long low bench heaped with cloths and bandages, with a pair of ewers and three basins stacked inside one another at one end. There was a wide window, like the window in the refectory two stories below, but facing south instead of north, looking out over the roof of a neighboring apartment and on across a jumble of peaks and towers, the city spilling downward from the sisterhouse’s Castle-shadowed perch.

The chapel’s ceiling was just beneath the infirmary floor, and the chanting rose through beams, plaster and the reddish tile beneath her bed. The same prayers she had sung with Temperance in the harbor shrine for Father Aldiff, but perfected, faultless, with Devotion’s harmonies spiraling at intervals. Rehearsal, practice for the imperial funeral the next day.

“You know, I was sick in this room for two months once,” Reverend Mother Concord said from where she stood, looking out the window, the high blue crown above her cowl matching the chimneys rising in her line of sight. “Sick with the yellow pox, the year before Princess Alsbet was born if I remember right. Just after I took my final vows. Half the sisterhouse had it, ten sisters died. Maybe more — twelve, thirteen? I don’t remember. A few like me were sick and didn’t die, but didn’t get better either – for weeks, months, more. I wasn’t the longest abed — that was old Sister Patience, dead these seven years. But not dead then. The day came when she walked out of here, scars all over her face, cheeks sagging off her bones. Blessed angels she was a sight. But she was alive, and how we cheered for her when she came for her first meal. How we cheered.”

The Reverend Mother turned to her, with her own sagging cheeks, her own faint line of yellowed scars above her owlish eyebrows, her kindly eyes.

“That’s the sort of place the sisterhouse can be, Fidelity. I hope you know that, by now. Doesn’t matter where you come from. How you came to be one of us. We really are bound together. Jophiel really does watch over us. When one of us suffers, we all suffer. When one of us is healed, we’re all healed. When one of us strays, we all feel it.”

Fidelity was trying to listen, trying to seem tractable and innocent, but the weight was still in her stomach, the heaviness of it, like a ewer she had meant to drink from and somehow accidentally swallowed. The nausea was gone, at least — after her performance that morning there was nothing left, everything she’d eaten for two days had painted the refectory’s floor. But still she didn’t feel cleaned-out as one usually did after purging in an illness. Her belly and her bowels were empty, but she was still carrying the weight.

“Child,” Reverend Mother Concord said, coming to the foot of her bed. “I just want to make certain that you’re happy. That you aren’t carrying any burdens in your life with us.”

Fidelity managed a wan smile. “Oh, Mother, no, I’m still so grateful to be here … I’m just sick, that’s all, just sick, I’ll be better, I’m just sorry to let Sister Recompense down for the singing …”

The eyes were kindly but unconvinced. “I spoke to Sister Excellence, she doesn’t see any sign of illness. I can send for a red sister to examine you, but I’ve seen my share of girls, I’ve seen worse than what you did to the refectory, believe me, and I’ve seen it come from nerves, often enough. And my task is to look after you, as I promised the Lord Chancellor. I know you wandered off on Winter’s Eve. Got lost they said. I told Sister Diligence not to punish you, I don’t think you were up to any mischief, but then this. Then this. So I came to see you, Sister Fidelity. Came to see you, my daughter. Just to see if there’s anything troubling you.”

Wandered off … She hadn’t wandered, really, she had just tried to help the poor drunk girl, it was only once the torches went out that she had found herself lost. And even then she hadn’t been wandering but searching, searching for the way to the stairs that her sisters must have taken, searching for the party that must have been dispatched to find her — that did find her, eventually, a stern Diligence and an anxious Temperance and several others, finding her where she had ended up, back at the doors to the chapel, huddled in their shadow, turning over what she’d seen but not yet clear on what it meant, carrying a mystery but not yet carrying the weight.

“Mother,” she said now, her eyes still drawn the older woman’s yellow scars, “I promise I’m just unwell. I didn’t wander off on Winter’s Eve, it was just ill-luck, I tried to help someone and got turned around, I explained it all to Sister Diligence and she said she understood …”

“Yes, yes, I heard. I heard. Was it very frightening, Fidelity? The dark nights are frightening. I just want to know what might be troubling you.”

It had been frightening — calling and calling without an answer, not calling too loudly for fear of the dark and what it might conceal, leaving the drunk girl propped up, following the remaining torchlight down one hall or another, seeing a figure and feeling hope that they had come to find her and then realizing they were shambling and drunk, someone to slip back from, back into the shadows, which was how she’d ended up there in the long hallway with the tapestries, watching and afraid …

“Fidelity? The way your eyes go distant, daughter — tell me what you’re thinking about.”

That was what Temperance had said to her the prior afternoon, sitting in the refectory with Gravity and Grace, their chatter dying away without Fidelity quite realizing it – you’re so far away, Fidelity, what on earth are you thinking about -- and then when she tried to answer her friend the weight became a vise that squeezed her stomach, squeezed her throat, and then she was on her knees and everything was coming out of her at once.

“I’m just thinking about the funeral,” Fidelity said, in what she hoped was a plausible tone. “I was listening to the singing and thinking about the emperor. It’s so awful, thinking that he was — that he was falling to his death just as I was wandering in the dark. And I was frightened. I was. I’ve had bad dreams. And also, also Reverend Mother, I’ve been thinking about the princess. She was so kind, so kind when we visited with her, and now, now I’m just thinking about what the princess must be doing right now, how awful it must be for her …”

It was plausible because some of it was true — the dreams, the awful thoughts, the fear. She probably would be thinking about Alsbet, in a world where nothing strange had befallen her on Winter’s Eve. And in a sense she was still thinking about the princess — not imagining what Alsbet was doing with her grief, but what she might do with the knowledge that Fidelity now carried.

“Oh, grief and all, I suspect she’s still thinking about her handsome prince,” the Reverend Mother said lightly. “I’ve seen three emperors, daughter, and his soon-to-be-majesty will be the fourth. You’ve never seen any but Edmund, angels rest him, but heaven called him home and we mustn’t find anything fearful in that. You’ll feel better. You’ll feel better.”

She sounded all sincerity, indeed she probably was all sincerity. She could be especially watchful for the sake of her agreement with Lord Arellwen and also see herself as a mother to Fidelity — there was no contradiction there.

But Fidelity’s mother was dead, and all the kindness of the sisterhouse couldn’t help with her secret. The holy wouldn’t know what to do with it, the rest couldn’t be trusted with it. There was nowhere else to put the weight.

“Well, Sister Fidelity,” the Reverend Mother said, brushing her lightly on the forehead, just below her cowl, “I will pray for you tonight. And I expect you will be back in your cell this evening, and with us for the morning Orison tomorrow. Yes?”

She nodded, all agreement, anything to clear the older woman from the room. And when she was alone again, alone with the empty beds, she forced herself to get up and walk to the window, feeling the heaviness everywhere inside, heart and bowels and liver, her throat when she swallowed, her lungs when she exhaled.

There was a bird, a single cardinal, strutting on the gutter running just below the glass. It eyed her curiously, a dream or image come to life.

“Do you know who I am?” she whispered through the mottled glass. Somehow its gaze seemed to change from curious to knowing.

“Do you?” she said again. “Do you?”

She was Sister Fidelity, and yet she was not. Her name was Rowenna, and she was the daughter of Edferth and Ilbet, sister of Willa and Hilwen, from the township of Balenty in the earldom of Bluehaven.

She was Rowenna of Balenty.

She was Rowenna of Balenty, and she knew who had killed her emperor.

That morning Alsbet rose early and went out from the keep into the frosty silence of the bailey. Two legionnaires stood stoically by the main gates, and a few servants hurried across the courtyard with loads of wood to feed the fires that would soon be lit in the kitchens and bedrooms of the Castle. Servants and soldiers alike were clad in somber black, and the sky above was a dull, chilly gray, like old silver in the attic. Snow shoveled days before was heaped in blackened mounds against the walls, leaving behind frozen earth and flagstones, with brown ice in the low places. All around the walls and towers looked worn and scarred, and in the morning chill the entire scene seemed laid waste by time.

Alsbet looked back and up, to the towers rising behind the keep and the falcons hanging at half-mast in the winter air. Then, tightening her cloak's clasp, she went down the steps and crossed the courtyard, moving toward a postern door leading into the west bailey. The soldiers there snapped twin salutes, and their princess nodded absently as she passed them and pushed the heavy door open, blinking in the sudden whiteness from snow uncleared and then glazed by freezing rain.

There were paths trodden down into a hard red-brown, and all around lay sheds and storage buildings, and cottages belonging to the grooms and stablehands, with small chimneys coiling smoke toward the glowering sky. The inhabitants were just coming awake, and they looked up from their tasks to stare curiously as the princess passed, a slim figure in black crunching lightly through the layer of frost atop the packed-down paths.

Alsbet moved on, with the keep looming on her right and the outer walls rising on the other side. The cottages ended and the brown bulk of the stable appeared, its dark wood supported by the stones of the outer wall, and she inhaled a faint whiff of straw and manure, the rank, sweet smell that cloyed this part of the bailey in summer.

A stableman appeared in one of the doorways, a grimy figure in brown leather banded in mourning black, with a cap tight around his scalp and a beard grasping at his pocked face; seeing her, he ducked his head quickly and vanished inside again. Alsbet wondered absently what he was doing — giving the mounts their morning mash, most likely, but she briefly imagined that he was responsible for preparing her father's horse to canter glossy-black and riderless all the long way from Castle to temple and back again.

Past the stable lay another low wall and door, and as the princess pushed through into a fallen-in, half-rebuilt extension of the Castle, she became more conscious of Matheld’s Tower climbing the winter air above. Averting her eyes from the spire, she stepped carefully through a gap in a crumbling wall, pushing aside the thorny branches that trailed down the broken stone, and came at length into her mother’s garden.

A pair of crows flapped away angrily from the bare branches of a rose bush. Otherwise, the garden was empty, but its midwinter repose was ruined by the footprints and the broken branches where people had crowded on the morning of her father's death. The spot itself was mostly cleared of snow, and the banner of their house had been staked down across the flagstones, the Montair stag rearing across an island of scarlet amid the winter garden to mark where Narsil’s emperor had fallen.

Alsbet crouched there for a little while, brushing slivers of ice from the stiff cloth. The morning air warmed slowly, and echoes from the crowded keep reached her ears even in this empty corner. A sentry walked the outer wall, whistling, and the guests who slept in the lower rooms of Matheld's Tower began to spill out onto the battlement, moving in clusters of fur and black cloth toward the causeway linking the tower to the keep. None looked down into the mesh of branches to their right, and Alsbet looked up in earnest only once — when she did, an earl and his wife were herding their two well-swaddled daughters along the wall, and one of the girls was singing to herself, her young voice struggling with the notes and her blonde braids jouncing …

I am not a child, Alsbet told herself. No more, no more, no more …

A slight breeze shivered the garden, and she dusted another mite of frost from the antlers of her father’s stag. She had come here deep in bright daylight after the feast, after the chamberlain and Gavian had woken her with the news, and stumbled through the gabbling nobles and frightened-eyed soldiers to find him, Edmund the emperor, stiff and cold and lying in a pool of crimson ice, his body limp and shattered, his face crushed into a ghastly pudding of flesh and bone. He had been half-buried, the adjutant muttered, looking away from her as he spoke — the snow had almost hidden him, but there was a flash of purple in the garden and a sentry spotted it just before eight bells that morning.

The men were bitter hung-over, Highness . . . I thought it’d be some lord’s cloak, or maybe an empty firework — nothing at all, really, but when men aren't sober, you know, it's good to keep them moving, especially in the cold, so I sent someone down into the garden.

The officer seemed apologetic, telling her this, while the black priests somehow materialized to hoist her father — her father's body, him no longer — onto a stretcher and carried him away. His defensive tones invited blame, as if he were waiting for her to wail and say that if only no one had gone down to look, her father might still be alive. Perhaps that was what he expected of women. Alsbet had wept a little as he spoke, the tears biting at her cheeks, but she had nodded and said that he had done well, and ordered him, or someone, to gather the council so that her brother might be informed and the great machinery of succession begin grinding. Then she had returned to her room and dressed in black, gone to Padrec's room and hailed him as emperor, dismissed Gavian and Aeden, and ordered a servant to tell Maibhygon that she could not dine with him tonight.

And since then, somehow, five days had passed.

“Princess?” a voice called.

She looked up, across the tangled bushes, and saw two figures approaching, one tall and spare, the other shorter and rounder and skirted — Aeden first, and Morwen her maidservant, rosy cheeks framed by dark hair in the iron light. Alsbet rose slowly, waving to them as Morwen slipped on a patch of ice and caught at the steward's arm for support.

“I’m over here,” she called.

“Are you all right, Highness?” Morwen called, her voice sharp and nervous-sounding.

“I’m fine,” she answered as they reached her, a little too sharp herself. “Just fine. What is it? Is something needed?”

“Well,” the maid said, kneading at her black frock, “it's only that it’s passing eight bells, and they'll all be gathering in the courtyard in just an hour . . . and you're not yet fixed up for it.”

“No one knew where you went,” Aeden added, with a hint of reproach. “You rose before your maids — they’ve been scouring the wing looking for you.”

She sighed. “And how did you know where to find me, Morwen?”

The plump young woman glanced at her companion nervously. Alsbet’s maids, she knew, were slightly in awe of Aeden, his keen intelligence and carefully curbed pride. Sometimes they joked about seducing him — “knocking master steward off his pedestal,” they called it.

They had other jokes, but those Alsbet chose not to hear.

“Ah … it was Master Aeden, highness. He suggested we might find you down here.”

He grimaced. “It seemed a likely place to look.”

Alsbet nodded slowly, and said she would be inside soon. Morwen bobbed her head and hurried back into the keep to call off the search, but Aeden remained, seating himself on the lip of a low stone wall, watching his princess stand in a dark cloak beside the rose bush and the staked-down banner.

“You’re still here, Aed?” she asked after a time, not looking up.

“I think you should come in, princess," he said gently.

"I said that I was coming. You don't have to worry — I'm not going to sit out here all day. It's too cold for that. And I haven't been doing this every day, since he died. I'm not going mad, you know, or anything.” A pause. “I’m not drinking, either.”

"But you’re here now."

Alsbet sighed and brushed a trailing strand of hair from her eyes. It was so difficult to explain, so difficult — but this was Aeden, not a stranger, and he had known both of her parents, he had been with her so long, he loved her.

“Yes, I’m here,” she said after a time. “I’m here . . . I don’t know. This place belongs to them —to both my parents. My mother’s garden, and my father’s fall. I don't -- I suppose that I’m hoping to feel them here, to remember them somehow."

Aeden was silent, and so she stumbled on. “But it’s not that I don't remember them — I do! It's only that … after my mother died, I remembered everything about her, everything she did or said all through my childhood, how wonderful she was — it was awful, to think of her gone, more awful than anything.”

He nodded sadly. “I loved your mother, too, Alsbet.”

"Yes, I suppose you did. Everyone loved her, everyone. People met her — and they fell in love, and that was settled. They were in love for life, even if they didn't realize it until it was too late, like my father.” She laughed weakly. “I wonder sometimes if I will ever have that effect on men. I doubt it — whatever I may pretend, I am not my mother. But — well, I was saying that when she died, it was the worst thing in the world, because I knew what I had lost. But now ...”

“Now?”

"Oh, Aeden," she cried, dropping her face into her palms, “I can't remember anything! I loved him so very much! So much, so much, but I don't feel sad, just empty, just — empty, like one of those hollow dolls the Skalbarders make. I don't have any happy memories of him, or none I can easily recall. When I think of him, I just think of him sitting up in that horrible chamber of his, with the drapes pulled, drinking and drinking and talking endlessly at me, saying nothing! And that’s all I can think of, and how can I miss that? I don't want to remember him that way, do you understand? I want to remember him the way he was before … I want to so much, but I just can't.

“And then what we’re about to do today, the speech we wrote — I’m just telling lies, Aed. Telling lies to help other people remember my father the way I can’t. Inventing grief from a brother who may be gone forever to mourn a father who I can’t remember as anything except a dark cloud over my life …”

“Statecraft is often the art of telling important lies,” he murmured, but she didn’t hear because she was sobbing, shuddering beneath her cloak, and he came over and held her and comforted her as he had sometimes held her so many years ago, when they had both been small in High House. And he talked about his own memories of Edmund, which were sparse but vivid: the emperor going riding with them, his spurs gleaming in the summer sun; the emperor sitting before a fire in winter, describing battles with the northern barbarians to his rapt children; the emperor meeting him for the first time, when the young Brethon had been frightened and skinny and missing his dead parents terribly.

“He said that I reminded him of a fish he had caught in the Mersana when he was a boy. ‘The scrawniest minnow I ever saw,’ he said, 'but it put up the best fight of any fish in my whole life, and in the end it slipped the hook and got away. So if you're anything like that fish, I’ve got high hopes for you, lad.’”

Alsbet laughed through her tears, and Aeden held her closer. “And then he told me that I was to protect you, princess, and that if I ever let any harm come to you, I had best fall on my steward’s quill, because I would be dishonored forever.”

“And you've done well, Aed,” she said, clinging to him, giving him the first real taste of happiness in many months.

"I know, princess. I know."

“You've been my great friend, you know — you always will be.” She lifted her face from his cloak, looking at him with those beautiful blue eyes, her face close enough to kiss — but never close enough, never never never . . .

“And I'll be all right,” Alsbet was telling him seriously, wiping at her tears. “I will, you know. I just have to get through the funeral, get rid of all this ... this muck. Because it was his time, the angels decided to take him, there were worse ways it all could end — and it's Padrec’s time now, his time here, and it’s time for us to go to Bryghala. So I’ll be fine, because I need to be fine, so that I can be his wife . . . Maibhygon's wife."

The crows circled Matheld’s Tower, raising their bitter dirge. “Do you love him?” Aeden asked softly.

She smiled sadly. "Not really and truly, I don’t think. But I will .— and he will love me. I intend to be happy, Aeden, in Aelsendar.”

He reached out and brushed a tear from her cheek, the drop damp on his fingertip, the intimacy thrilling and terrible. “Promise me that, princess. Promise that you will be happy.”

“I promise, Aed.”

They went in, then, because the bell was pealing, and the funeral was almost upon them.

The wind was at their backs all the long, frozen way from the Castle gates to the temple’s seraph-guarded doors. Twenty mounted legionnaires led the procession, and the hearse followed them, a black wagon driven by the black priests that creaked and groaned and seemed to swallow up good cheer. The riderless horse cantered just behind, and the lords and ladies and Castle folk walked after, their joints tight with the cold, and their eyes hard like the beaten sky.

Padrec led the mourners, his head bare and waiting for the crown it was owed; Alsbet followed, neck bent, face hidden beneath a flowing veil. Prince Maibhygon, flanked by four of his knights, strode a few paces behind the Montairs, and the council, their medals of office gleaming gold against their inky robes, made up the next group in the procession.

Then came the dukes and ducal heirs — ten of them now, black-bearded Donff mac Carroad of Mabon having come in haste through the Thornhills for the funeral, his party arriving just this morning with lathered horses and windburned cheeks. Benfred and Cresseda led the group, the Montair stag and the Argosan rose rippling as the wind caught at their respective cloaks. Then came the Heart dukes, Jonthen and Cethberd; then the Ysanis, Donff and young Coallen; then Eldred and Baldwen; and then finally the two Brethons, close to one another as if for mutual protection.

The crowds gawked at the dukes and the duchess, picking out Cresseda and Jonthen Cathelstan and Cethberd quickly because they mattered; watching the Brethons warily, as if they expected the conquered nobles to turn on them without warning; dismissing the rest as unimportant and unimpressive. They stayed to stare at the bright clothes and foreign faces of the ambassadors, who passed next, but they began to melt away during the collection of earls and lesser lords that followed. By the time the minor nobles gave way to the Castle staff, the city-folk not on their way to the temple were hustling to the shrines scattered around the city, where separate services for the departed emperor would be conducted. Aeden, leading the stewards alongside the lord chamberlain, saw emptying streets and the backs of the empire's nobility.

The temple doors yawned darkly, swallowing the procession and the crowd that swarmed in after them. Inside, cold currents wafted around the coiled stone pillars and frozen-faced statues of blesseds and angels, chilling the nobles sitting in silence on the pews and the commons jostling in the vast stone spaces in the nave. The liturgy began with grim, sorrowful pomp, and the stained-glass faces of the nine archangels filtered the weak winter light as they looked down on the altar, on priests and sisters in their colors, on the sea of black-swaddled mourners, and the coffin where Edmund lay.

After the introductory prayers were finished, after the blue sisters chanted the lesser orisons, Ethred, his voice quavering a little, blessed the company, spoke a few personal words about an emperor who had been his cousin, and then invited the eulogists to come to the rostrum. Lord Arellwen spoke briefly, and Cresseda and Baldwen both offered polite words — and then, to some surprise, Aengiss mac Cullolen rose and stalked to the rostrum, his bootheels clicking and his shaven head gold on the flame-lit altar.

“I will be brief,” he declared sharply. “I fought with Edmund Montair for ten years, and for Edmund Montair for twenty. We had disagreements during that time, but he goes to his reward a truly great emperor, a ruler whose name will be acclaimed for as long as our empire endures. It was my honor, my great honor, to serve him in war and in peace alike. No man was fiercer in battle, and no one will ever question his magnanimity in victory. I pray that the archangels will send many more such men to rule in Narsil.”

Aengiss paused, his fierce eyes roving across the nobles crowding the pews, and when he spoke again his voice had dropped an octave. “And I pray as well that heaven will send loyal men to serve them.”

The old soldier descended, and now Alsbet rose, black-gloved and beautiful, and took his place. Aengiss’ brief address had left a low buzz in the crowd of the nobles, but for the mass of commoners the political overtones of the general's words had passed unnoticed; the appearance of their lovely, popular, and twice-bereft princess was much more important, and they stirred and listened as she began, haltingly at first, and then with gaining confidence, describing Edmund not as a soldier or a ruler, but as a father to his people.

As she spoke, reading and expanding on the words that she and Aeden had crafted together over candlelight, the last three years of his reign were forgotten, and what the crowd remembered was Edmund, young and handsome, ascending the throne — Edmund, marrying his beautiful bride in this very temple, with all the city crowding around to witness it — Edmund holding his infant son and heir before cheering crowds — Edmund returning victorious from the first great war in Brethony, bearing spoils and captured standards — Edmund the well-beloved, Edmund the conqueror, Edmund the Great. Through all the long speech, Alsbet could think of nothing but pools of spilled wine, drying into ruddy stains on her father's tables, but the mass of mourners knew nothing of that, and there were tears in many eyes by the time she finished.

“Before my father died,” she said at the end, “when we thought we were only gathering to celebrate a betrothal, a letter came from my brother Elfred in distant Antiala, where he studies with the great schoolmen of that city. He was too far from home to return for the betrothal, or for this far sadder day, but I think it fitting that we should hear his words. Elfred wrote to say that when my father sent him away, he felt betrayed, because he had not wished to be a scholar, but rather a warrior. He felt that the emperor had somehow failed to be a true father to him …”

She was unrolling a parchment as she spoke, a scroll that looked worn enough to have endured a long, air-borne journey from Antiala north over the Redwine Hills, over Argosa and the Heart to Rendale, the birds braving sleet and wind to bear an imperial prince’s message.

“This is what he said," Alsbet said, dropping her eyes to the scroll. “Once, sister, I was angry at our father. But through my studies I have come to understand the terrible burden of kings and emperors. Rulers, you see, cannot be fathers to their children in the way that other men are, because they must be the father to an entire people, who are given to their charge by the archangels themselves. However much they might wish it to be otherwise, they must think of every child born under their dominion as they do their own child, born of their loins. I cried when I was sent away from my home, but I imagine that if tears were allowed him, my father would have wept far more, knowing what he had been asked to give up when he assumed the throne.’”

She paused for a moment, and then said, in her own voice: “My brother was writing to describe the responsibilities that I would assume, that I will assume, as a princess and someday a queen in Bryghala. But what he said deserves to be heard as we mourn my father, your emperor, Edmund the Great, because he was a father to more, to many more, than just a daughter and two sons. And as we commit his soul to the heavens and his body to the earth, it is not only our family that has lost its father — it is all of Narsil.'"

Most of Rendale's people had never felt Edmund Montair's hand directly in their lives. But as Alsbet descended, her knees still quivering a little with nervous energy, to take her seat beside Padrec, there was a great storm of weeping in the vast cold temple, a hushed murmur of tears watched mutely by the sad-eyed archangels above.

Padrec's eulogy, which came next, was brief and swiftly forgotten, as he intended.

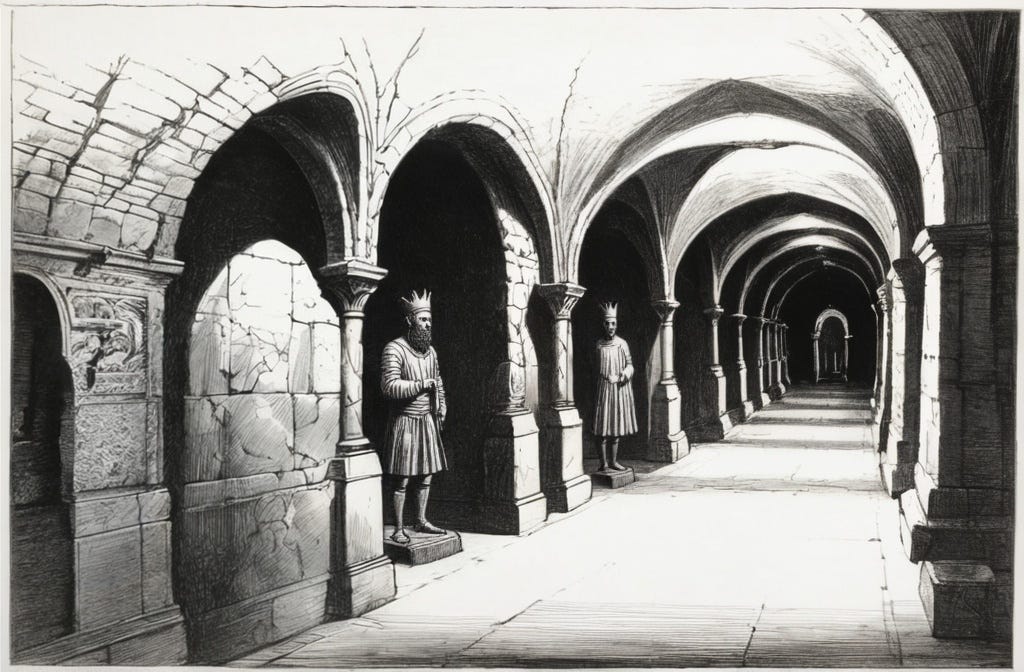

There were more prayers after he was done, followed by a lengthy, incense-thick blessing of Edmund’s earthly remains, and then the mourning chants from the blue sisters. Then there was the orison for the dead, five black priests chanting together, a long grim appeal to Azriel, Archangel of Death. In all, it was more than an hour before the hearse was reloaded and the procession wound its way back to the Castle, shedding its crowds along the way and finally reaching the heavy, iron-studded gates that welcomed Edmund back into his birthplace and home. The nobles and castle staff milled in respectful quiet in the main courtyard while the dukes and the imperial family followed the coffin through another gate into the west bailey, to the doors that opened just beneath the outer wall of the Castle’s chapel, and then down a long flight of steps between watching stone falcons into the bleak, whispery dark below the keep.

Candles had been lit all the long way past the tombs of long-dead monarchs, but it was bitingly cold there, with statues of Montairs and Barrawelfs and Cristises staring sightlessly, and the upper world seemed far away. Edmund’s stone likeness, carved nearly seven years ago, stood on the left side of the aisle, his hand on his sword hilt as he looked across the flagstones to meet the gaze of his father Jonthen. Beyond these two latest emperors the black priests gathered, chanting again; past them, the hall stretched away into an unlit darkness where few stared for long.

After a time two priests lowered the coffin into a space below Edmund’s statue, and then fell silent as Ethred sprinkled the corpse with earth and water and pronounced the blessing. Then the priests shoveled dirt from a nearby wheelbarrow until the coffin was covered, and then lowered two large flagstones onto the grave, settling them into place with a loud clatter and thud.

Ethred turned from the statue and the grave, his jowls pale in the candlelight, and raised his hands to bless the company. When he spoke, it was in Mandoran:

“Serrinavas os srata Edmund, no'ameharis, as ansa os serrinavasin no'vascinati, pon ostra ansa koritabis.” Let us remember our brother Edmund, our emperor, and remember also our sins, for we too must die.

“Ostra ansa koritabis,” Padrec and Alsbet, the priests and dukes repeated, and bowed in unison as the Archpriest departed, trailed by lesser clerics. Then the black priests lit the tapers at either side of the newly sealed grave, and murmuring prayers, departed in their turn, leaving the emperor’s children and his nobles in the catacombs.

Once all the lords present for an imperial funeral were expected to keep vigil at their ruler’s tomb, but that tradition had passed as the empire expanded and its lords grew too numerous to fit inside the space. Still, most of the dukes intended to remain as long as possible in the crypt, if only because no one wished to be the first to emerge into the crowds and intrigues of the Castle above.

But the cold crept into their bones, and the darkness beyond the statues and candles seemed to grow and throb as time wore on, and the words of the prayer echoed in their ears

Ostra ansa koritabis

We too must die

and they remembered the hushed crowd in the temple, and Edmund's black-draped coffin, and the chants of the black priests — priests who would chant for them someday in Felcester and Erona and Sheppholm and Ysan. The candles cast long shadows across the imperial likenesses, and as the silence stretched and grew oppressive, the dukes began to think of their sins. Jonthen Cathelstan thought of his gluttony and his casual possession of farmgirls on his country estate. Eldred Gerdwell thought of the headstrong cousin he had assassinated with a slow-killing poison seven years before. Baldwen Rilias thought of his wife and the petty viciousness between them that had lasted the better part of three decades. Benfred Montair thought of murder and treason, both still only anticipated, both too far along to stop.

Ostra ansa koritabis

We too must die

A draft whispered through the hall, and the dukes slowly slipped away, up into the clean air and falling darkness up above.

Alone now, Padrec and Alsbet stood in silence. For a long time, the only sounds in the crypt were the whisper of a draft that set the candles and torches bobbing and the distant drip of water far beneath. When Padrec finally spoke, hours seemed to have passed, and strange echoes chased his words down the hall.

“I wish Elfred could have been here.”

Alsbet looked at him, but he was still staring at his father's statue — at the firm, handsome features, the long cloak falling around armor, and the falcon crown banding the head with stony wings.

“I do too.”

“I never got to see him before he went away, you know,” Padrec said absently. “Sometimes in the last two years I thought of going south to Antiala. Just not seriously enough to do it.”

“I’m sure he would have liked to see you.”

“Yes … we were so close, once. You remember — at High House? They couldn't keep us apart. We would go angels-know-where together — exploring up in those high pastures, chasing mountain goats, or getting chased by them. And we made such plans, for what we would do when we were older ... the most detailed plans.”

Alsbet looked at him sadly, wondering if it were possible to strip away the veil of years that separated them. “He was very unhappy to leave,” she said after a pause.

“I’d imagine.” Padrec chuckled bleakly. “Funny … he was always more excited by the idea of war than I was, back then. Neither of us really knew what it was, of course — and now maybe he’ll never have to find out.”

“He’s lucky, in a way.” Her tone was probing.

"Lucky? I don't know about that. Lucky not to fight, well, I’d say to that —” He paused, on the verge of a flippant reply, as his eyes lit on his father's stone hand, resting on the sword's pommel. It might have been a trick of the light, but the hand seemed to clutch at the sword, as a drunkard clutches his bottle.

“I don't know,” he said finally. “War is the sort of thing that a man has a hard time wrapping his mind around.”

There seemed nothing to be said in reply to that, and Alsbet fell silent. In the torchlight she could see the small memorials to the left of her father’s statue, the little seraphs carved for Elfretha and Megwen, the sisters she had never known. She had learned of them from someone in her girlhood, and sometimes — especially before Aeden — they had been her imagined playmates, so that she too could pretend to enjoy what Elfred and Padrec had together, the games and fellowship.

“I was surprised he wrote to you like that,” her brother said. “But I’ve sent for him, you know. I thought he might come unwillingly, but he is heir to the throne until — until I take a wife. We need him close, whatever he has become. But maybe he has become wiser than us, judging from that letter.”

“He didn’t write that letter,” Alsbet said quietly.

“What?”

“I needed a flourish, in someone else’s words. In a man’s words. We thought— Aeden and I thought that we could give that pretty speech to Elfred — he wouldn’t complain. His real letters have been occasional and, well, less eloquent.”

Padrec was staring at her as though she were a stranger. Then he clapped his hands together and laughed. “Sister! That’s terrible. You have learned something dark, haven’t you, presiding over this awful frozen place! I would not have thought it of you. I never thought my lovely little sister would grow up to be a politician.”

“I have been alone here for a long time, Padrec,” she said, in a tight, cold voice. “I have a few friends and that is all. I have done my best for our house without any real family to guide me.”

“Without me, you mean? Alsbet, I accept the charge. I accept it. Azriel, I cannot believe that was all fraud … no, I accept it. Listen: It can be different. It will be different, once I am crowned. We can bring Elfred back, and we can all be together — all the falcon’s children, finally come of age. Your loneliness — I’m sorry, Alsbet. But it will be different from now on. Here and in Brethony.”

“But I won’t be here, Padrec,” she said, with a faint, sad smile. “I’ll be gone very soon, you know. I hope we can see one another in Brethony, I hope so very much. But I know that I may never see Rendale, or my — our father's tomb again, after I go to Bryghala.”

“After you go — yes.” There was something odd about Padrec’s voice, something not quite right that made her turn her eyes and look at him squarely, trying to read his candlelit expression. The dripping sound had ceased in the caverns she imagined yawning below them, and the silence pressed close as she waited for her brother to speak, a feeling of dreadful anticipation coiling up within her.

“Alsbet,” he said at last, and she exhaled sharply — she had been holding her breath.

“Yes, Padrec.”

“Sister. If you want to stay down here with me, to keep vigil —” He paused. "If you’re going to be down here tonight, I think it's only right that I tell you something.”

“Something?” she said weakly. “I don't know what you mean. You can tell me anything, Padrec —”

“No, no you don’t,” he interrupted. “There are some things I can't tell you — because of who I am, and what we have to do . . . oh Mithriel, that sounds pompous. What I mean is, you don’t know what . . . damn it all, this is hard to say."

“Why?”

“Because it is! You'll understand when you hear it. But I don't know—”

“Just say it,” Alsbet told him, almost in a whisper. And so he did.

“You're not going to Bryghala,” Padrec said firmly. “You’re not marrying Maibhygon.”

She stared at him, and past him into the long darkness stretching behind his unhappy features, and he looked away from her and back at Edmund’s statue and he began to talk, faster, faster, and meanwhile the water was dripping again, or maybe it was just that the words were pouring like a torrent from her brother's mouth while she thought of streams and springs, babbling and bubbling far below, in dark caverns where goblins lurked, and deep lakes and precious gems.

He was telling her that Maibhygon was wicked, and terrible, and was part of some complicated conspiracy with Cresseda to topple her father, or rather to kill him, and kill Padrec as well, and somehow Paulus was mixed up in it, Padrec’s handsome friend who all her ladies swooned for, and she heard it all and yet did not hear it, until her baffled mind seized one drop out of the cataract —

"Did you say that Maibhygon . . . that Prince Maibhygon killed our father?"

“Yes,” Padrec said eagerly, turning back to her, “yes, he did, he killed him — or ordered one of his men to it, one of the Bryghalans, which comes to the same thing! It’s just the same as on the river, just the same hatred, they’re all cultists, the cult is Bryghala, the King of Hills and Water — he hates us, Alsbet, underneath all his courtly manners Maibyghon must hate us, and he wanted revenge on our father and on all of us, for what we did, because we won the wars …”

“No,” she said softly, suddenly dizzy, yet strangely calm, “no, no, he didn’t. You don't know him, Padrec — I do. He didn't do it. Cresseda — I don’t know about Cresseda, and her ambitions. I don’t know. But you’re wrong about Maibyghon, I’m sorry, but you're wrong.”

“No!” he almost shouted. “No, no, I’m not wrong. Know him, how can you know him, he’s been here a tenday, Alsbet, a tenday. He hated us — hated the empire — wanted revenge! He made a bargain with the Vernas to kill our father and kill me too, later, and then their Ambarian would be emperor, he would probably be married to you, you’d be married at swordpoint, and Bryghala would be given something …”

“You are mistaken,” she said firmly.

“... and I have proof!"

Past him, the darkness seemed to stir, and Alsbet felt a crackling heat trace the rash that scarred her black-gloved arms.

“Proof,” she repeated, still calm, still as ice. “What proof?”

"Everything! Testimony, everything you could want — angels, I told you, they tried to get Paulus to kill me! They thought they had bought him, with their southern silver! They thought they owned him! They’re all guilty, damned by their own hands! It is proven!"

“You’re mistaken," she heard herself say again, but it felt as though her own voice was coming from far away, a weak, mouse-like sound in the dark and silence of the crypt.

“No!” he cried in frustration. “No! You must believe me, sister! You must!"

You don't believe it yourself, Alsbet almost said, tried to say, but the words would not quite come. She tried to look at her father's statue, but Padrec had her by the shoulders now, and she twisted away from his gaze and saw the unlit hallway stretching behind him, the dark stirring and churning, like the surface of a mountain lake under a thunderstorm.

Her brother paused and drew breath. “I promise you, sister,” he said gently, “that they will pay, all of them, for what they did to our father — and what they did to you. I swear it. Tonight is the beginning, the time to settle accounts, and while we are down here, they are being arrested … Cresseda, the traitors who support her, the ones we suspect, and Maibhygon. And not only here in the castle — all the traitors are being arrested, all over the empire, by my command. The riders have gone out, the birds — they have spies everywhere, agents everywhere — the commander in Caldmark, Veruna, he’s one of them, and there are others, and some we’ll exile, but some must die … because they murdered our father, Alsbet, and that's treason, and regicide, and, and … are you listening to me, sister? I tell you they killed our father!”

The roiling darkness was a wave rolling toward them, and there were sparks inside its black waters, dancing stars. “And Maibhygon?” she heard herself say.

“I will not execute him,” Padrec told her. “But he will never leave, he will be a prisoner here forever, forgotten, a ghost in our dungeons — I will send his men away in the spring, and then I will lead an army against Bryghala, and exact vengeance . . . exact justice. For what they did to our father, they will be wiped off the earth, Alsbet. And then Brethony, all Brethony, will be united. All of it united, all of it ours. And you shall marry anyone you please, sister, and so shall I, and Elfred …”

He released her, and reached out to place his hands on Edmund’s statue, his palms sliding down his father's arms to grip the stone scabbard of the dead emperor's sword. “On our father’s grave, Alsbet, I swear it!” Her brother was breathing hard. “Well? Do you understand? Will you say something, by all the archangels? Don't just stare at me … you cannot marry him, you cannot go to Bryghala, they killed our father, Maibhygon killed him, I tell you! You will have another husband, I promise, better, finer, true … speak, please speak to me, Alsbet …”

She felt the roar of the coming darkness, and heard herself ask:

“Did you have our father killed, Padrec? Is that what all this is for?”

He stared, and then struck her, not a hard blow but still the crack echoed down the hallway. Alsbet fell, a thin crimson thread running from her mouth, and she felt the wave of darkness surge over her at last.

Her brother's face crumpled. “Oh, angels, I didn't mean that, please, I'm sorry, why did you say that …”

But Alsbet did not hear him or see him — she was lost in the dark, feeling the cold of the place, smelling the loam, frozen on the surface but alive and pulsing down below them, below the Castle where the ghosts slept. Her whole body was afire, and stars burst like fireworks in the black — and behind them, beneath them, all around were the voices of the dead.

“Alsbet,” Padrec gasped, bending over her, “oh Gavriel, are you all right …”

The statues, the faces carved into the walls, they were all alive here, and she saw her father and grandfather, and all the other Montairs, and their wives and children with them, and the other dynasties, all whispering and crying and shouting and gibbering like ghosts, because they were ghosts, their faces pale and whirling and then merging, their voices merging, until all she saw was a Fool’s face, a thing of rags and patches, his eyes green like emeralds in the dark . . .

“Alsbet, damn it, I have to stay down here, I have to keep vigil, don't do this to me, come back. Alsbet …”

She surfaced for a moment, hearing him, feeling the flagstones hard and cold beneath her — and then they fell away, the whole world falling with them, and the dark ocean swallowed her again.