To Dernbridge

The Falcon's Children, Chapter 25

The snow came with first light, the sky’s steel darkening to pewter and then releasing a steady fall that lasted hours, into the afternoon, until the advance guard reported that their pace would leave them short of Rendale by nightfall no matter how hard they pushed the men.

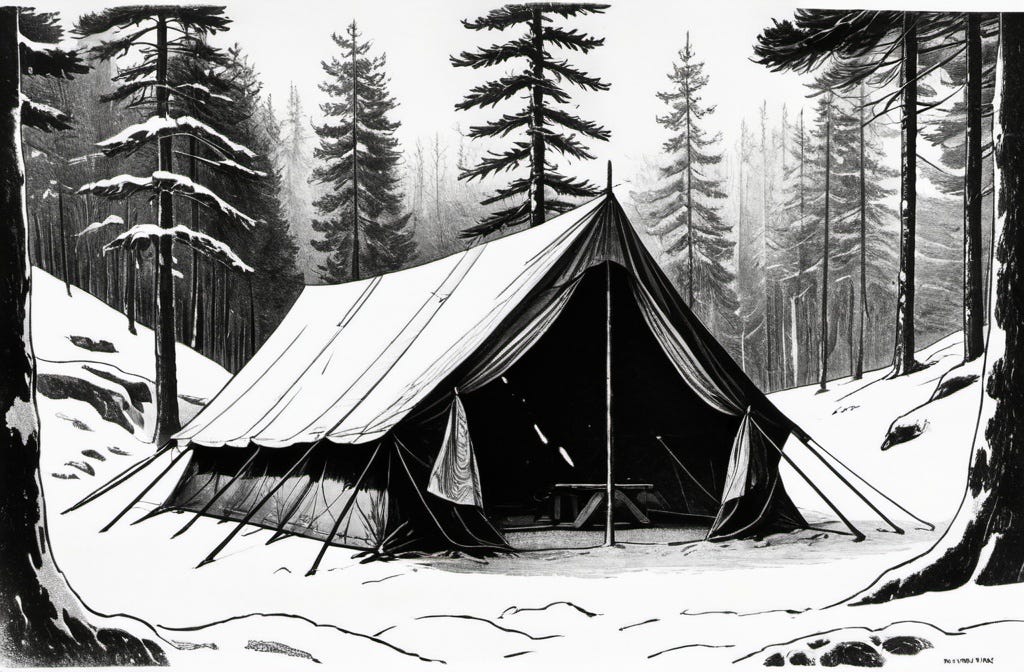

So the Old Hound ordered a temporary halt, in a place where a narrow ridge ran down from the mountains and a long stand of black firs offered some shelter from the weather. The legionnaires threw up a tent where the trees were thickest and the snow lay light on needled ground, and while the army rested and waited for the snow to taper, the general and his captains and Benfred Montair convened under the billowing fabric, blowing on their hands while the white flakes blew and swirled outside.

“I would have pushed all the way,” Veruna said to Benfred, “but if what you say is true there’s no surprise to be gained, and no point in showing up at the walls in the dark with the men all winded.”

The tone of that if what you say is true suggested a continuing suspicion that it was not. That had been Veruna’s first reaction when Benfred had been brought to him in the wee hours of the night, exhaustion dragging at the duke after his mad gallop north from Rendale, astonishment obvious on the general’s face.

Is this some stratagem from Aengiss? Veruna had barked at him. A false defection to buy time for an escape?

It had taken a long conversation to convince him otherwise, a conversation that had revealed more of Benfred’s own role in the Argosan plot that the duke had intended to expose — and still Veruna clearly did not fully trust him, even though he was in the Old Hound’s tent, in his councils, standing with his three captains while they laid their plans. Even though Uffish and Edme rode alongside the Old Hound’s legionnaires, through whom he had been paraded earlier, to cheers — a Montair duke in the flesh to boost their morale and make them believe that their mad rebellion might work.

Veruna’s trust doesn’t matter if this works; Cresseda’s trust is all that matters. And the strong chance that it wouldn’t work, the strong likelihood that only death waited for them at the end … well, that was entirely unaffected by the unburied suspicion in the Old Hound’s gaze.

“Do we go all the way to the walls in the darkness, then?” This was Mulias bar Sedura, southern enough to have an olive cast to his face even in the winter, with curls fringing his baldness and coiling in his beard.

Benfred did not know him, nor Pter, the general’s quick and wiry adjutant; he knew the other two captains a little, the scarred and brown-toothed Dethferd Rendell because he belonged to an old Heart family, and Berenek Skorshi, a grim-faced Skalbarder, because he had served in the Falconguard as a younger man when Benfred had been more often in Rendale and the Falconguard had been more often in the south.

How much of their commander’s suspicion they shared he couldn’t tell; Rendell had been friendly to him, the others mostly spoke as if he wasn’t there. If he was to think as a conspirator he supposed that he should be cultivating them, or Rendell at least, against the moment when he needed to assert himself within whatever kind of rule they ended up establishing — “they” meaning him and Cresseda, or him and Veruna, or the three of them together, depending on what befell in the next few days.

But at this moment he felt less like a conspirator than an old man, old and tired and too long in the cold, and the idea of playing off these soldiers against one another seemed perfectly impossible, like climbing a ladder to the highest heaven and bearing back Mithriel’s sword for a single combat against Padrec.

“… have to close off the southward road first, nothing else is more important,” Skorski was saying. “It may be that Davian’s riders can get around the walls, outside of arrow range, and head south in search of signs of flight; the land might allow it, depending on the weather. But if not, or if the Falconguard moves to block us …

“… then we have to take the city, and swiftly,” Pter said. “So all depends on whether Aengiss decides to defend the city walls or not. If he does I’d take it as a sign that our birds have flown and all he cares for is delay.”

“If Padrec has flown it will be a pity that his grace here did not keep to his original arrangement,” Sedura said, flicking his eyes at Benfred.

The Argosan captain wasn’t wrong: It would have been wiser if Benfred had sent Edme and Uffish and the rest of his own men south while he rode north alone, returning to the original plan and interposing their small force between Padrec and any possible flight south. What was his excuse? Confusion, uncertainty, a sense that Padrec was well dug in and wouldn’t flee, fear of taking the north road alone, fear of coming to Veruna alone — it was all still a mistake, and another reason for Veruna’s suspicion, another weight on the scale against him.

The Argosan was still talking. “… and we won’t know for certain if Padrec is still within the Castle until we take it, or whether his grace’s flight to us changed …”

“His grace and I have discussed the matter,” Veruna said curtly. “Regrets are useless in campaigns. So yes, the city — Leftenant Davian will have tried to skirt it by the time we reach the northern gates, so we should have some sense of how it’s defended, even by night. If he sends riders back with word he’s cleared through to the southern road, well, then we can wait for morning. If he’s turned back somehow though, we could consider a night attack …”

There was a noise of hooves in the snow outside, a sound of voices, and an officer Benfred hadn’t met yet came in, his cheeks flushed pink, snow dusting his helmet and shoulders.

He banged a salute, brushed at his armor: “M’lord general, we have more company.”

“Aengiss?” Veruna barked. “Are we attacked?”

The officer actually grinned at that, his mouth going lopsided. “No, m’lord, nothing like that. But they are from Rendale. It’s the princess … it’s her imperial highness Alsbet, m’lord, and Prince Maibhygon, the prince of Bryghala. Davian’s men just brought her — said they’d only gone a little way on their latest foray when they met her party, coming up the road, pushing their horses …”

“Alsbet and … Maibhygon?” Benfred broke in. “What — who else is with them?”

“Just a handful, m’lord – her captain, Gavian, a handful of men, a pair of Brethons, I think, an old woman … she’s not looking well, looks like a night’s ride been hard on her. But the princess — well, we’ve got a fire going for them, we weren’t sure what to do, shall I bring them up …?”

“No,” the Old Hound said quickly, over the mutterings of his captains. “No, I’ll go to them. Lord Benfred, Pter, with me, if you will. The rest of you to your men; whatever this means we may need to make ready to push south hard.”

So Benfred followed Veruna down through the makeshift camp, feeling the snow burn his cheeks, trying to keep up as the general stalked rapidly downhill.

They reached a stand of firs close to the road, pushed through the trailing limbs, and found a sheltered blaze, built on a floor of pine needles where frosted pine cones gleamed like Winter’s Eve treats. The cones crackled and broke beneath their feet, the party around the fire stirred and turned to meet them, and from out of a cluster of huddled cloaks bodies separated and faces came into focus: A collection of hard-bitten soldiers; a veiled woman in what looked like a blue sister’s habit; Alsbet’s narrow-faced steward; a wizened woman with a beaked nose and the look of age pushed beyond its strength; and beside her Maibhygon mar’ab Daenab’yr of Bryghala.

And Alsbet — his niece, he always thought of her, though she was really his second cousin, a cousin he had tried to advise and cultivate for years, during his desultory attempts to be a good and loyal Montair, but without much reciprocation, perhaps because of the limits of her age and sex. A pretty girl, pretty enough to be called beautiful by some, but neither as lovely nor as impressive as her dead mother; a graceful hostess, and a credit to her father, but a pale creature, too, with shadowed, unhappy eyes; a clever girl, clearly, with a better head than her brothers for some matters, but without the ambition or experience required to be a real player in the game.

But now she was here in the snow and cold, pushing back her hood and exposing the sad eyes he remembered, but something else as well, something different in her features and her gaze. Perhaps it was only the flush that the cold brought to her cheeks, but she looked more like Queen Bryghaida, more like the fox-faced Brethons in her mother’s lineage — and she appeared fierce, somehow, though perhaps that was borrowed from the armed men around, or perhaps he was being fanciful in his exhaustion, his old man’s bafflement at how events were falling out …

“My Lord Varelis,” she said, and her voice was bell-clear, even imperious, despite the wind. Then her eyes flicked to him, and he could see the curiosity, but all she said was: “And my dear uncle Benfred. An unexpected pleasure.”

“Princess Alsbet,” the general said, dropping his head briefly. “Welcome. You'll forgive me I don't fall to my knees, I hope — the ground isn't suited to it today.”

“And your allegiance to my house is somewhat shaky, I believe,” the princess said coolly.

“You might put it that way,” Veruna said with a slight chuckle. “But if I may ask about about your loyalty, princess — what brings you out in weather that isn't fit for a mountain goat? Were you hunting, perhaps, and lost your way? With your intended, whose acquaintance I am very pleased to make …?”

Alsbet smiled. “Ah, but we are exactly where we wish to be — with a man who opposes my brother.”

“I see,” the general said, in a tone that made it amply clear that he did not. “Perhaps … I mean, we would welcome you to our cause, highness, but I am not, I would …”

“You would ask why I wish to see my brother toppled? Why, that’s very simple. You may know that my betrothed was arrested — along with others, of course — on charges of plotting to kill our father, your late emperor.”

Is this all for love? Benfred thought. Betraying her house for love …?

“Which I take to be false charges …” Veruna was saying, with exceeding caution.

“Which are certainly false charges,” Alsbet agreed. “My father, you see, was killed by my brother’s orders. Padrec killed our father, and I have witnesses to prove it.”

The gasp from Veruna’s adjutant was audible. So, Benfred feared, was his own.

The Old Hound himself was very still, while the fire crackled and Alsbet fixed him with her strange, bright-blue stare. Then, slowly: “His Highness Padrec … had your father killed. It wasn’t an accident.”

“Oh, no,” she said, “no, it wasn’t that,” and maybe there was a catch in her voice, but then it hardened, “no, he killed him, and so whatever your own sins, whatever your own loyalties, you must bring him down, my lord. You and all the empire.”

“He murdered Edmund.” It was Benfred’s voice now, strange to his own ears. “Padrec murdered Edmund.”

“It was done on his orders, and I have the testimony of a witness, and my own certainty.”

“And you want me to bring him down,” Veruna said. “Bring down a parricide . . ."

“I do.”

“You want to help me bring him down, and you have proof that he killed his father, murdered the emperor …” The general’s voice was rueful, as though the cosmos somehow amused him, and Benfred felt an eager, almost-hopeful feeling, which seemed wrong with his niece standing there so fierce and sad and righteous, but it couldn't be helped, he looked around at the men and the tapering flurries, and thought, for the first time in days, that maybe it would turn out all right.