Westward

The Falcon's Children, Chapter 31

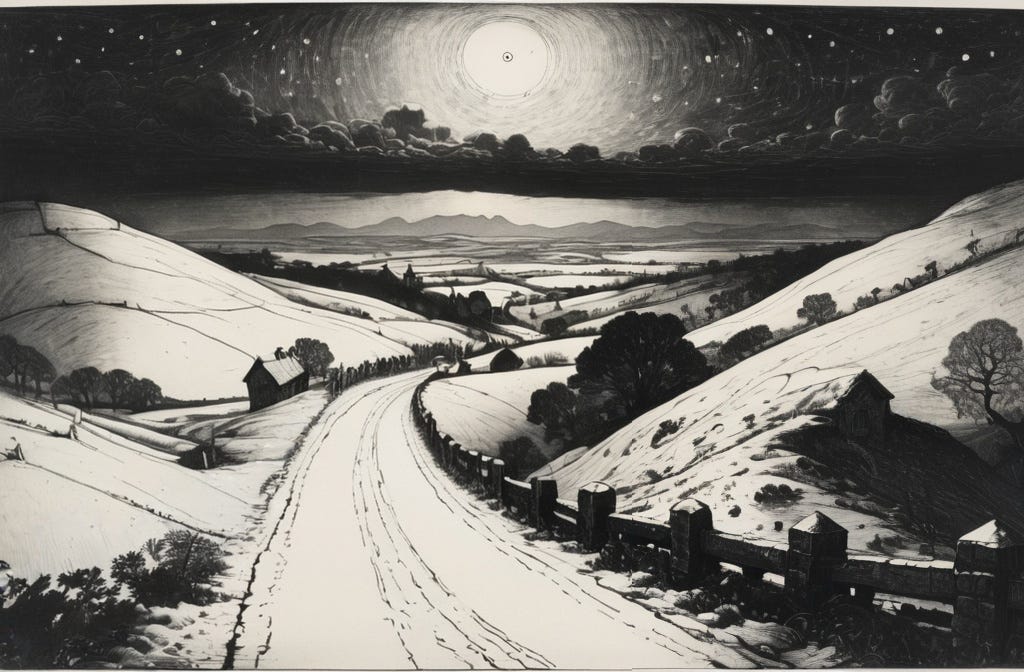

When she awoke she was cold. But then every wakening was cold, now, even wrapped up in blankets, everyone lying back to back in miserable intimacy around the embers of their fire. The cliff was above them, while pink dawn was infusing the trees further down the slope. Sitting up in the growing light she thought she could make out the path they had followed down the afternoon before, a track cut into the cliff that zigged and zagged, not too steeply, but so narrowly that only a fool would attempt the descent in ice, in winter.

Only a fool, or people with nowhere to go but forward, nothing behind them except doom.

Her cloak was torn at the fringes, filthy everywhere. Her skirts were fraying. She would need new clothes soon enough — except that how would she get them? Wander up to the first castle in Ysan, knock at the door, and ask if they had any appropriate dresses to spare for the princess of All Narsil?

In her dreams she sometimes found herself once more dressed in finery, back in the Castle, presiding in the great hall over some crowded ball or revel. Sometimes her father was beside her; sometimes Maibhygon. Sometimes the chair beside her seemed to be occupied by a stranger, but she found it difficult to look sideways and see his face.

There were many dancers in the dream, circling and circling; sometimes they were the familiar faces of her courtiers, sometimes they were masked, foxes and birds and bears and cats. In every dream she sensed that Paulus bar Merula was out there among the dancers, hiding his smirk in the crowd or behind a mask.

In one dream she managed to turn sideways to see the mysterious figure beside her, only to find that he too wore a mask — a stag’s face, antlered, that turned to meet her eyes …

“Are you all right, princess?” It was Aeden, offering his hand to help her as she wobbled briefly. She let him lift her up and out of the dream-memory, back into the harsh reality that was written on his face — the deep circles, the sharp features turned to gauntness, the change in just a few short days.

They were all changed, all of them. And if the angels favored them — something she sincerely doubted — the journey had only just begun.

Around her the makeshift camp was being picked up, Beren chivvying them, the pink light turning gold now, spreading like gilt over the forest. The Brethon knight, Baerys, was with the horses. Maibhygon was helping Guernys, as always now. Alrend was bending over Fidelity, checking her fever and her pulse.

She was about to cross to Beren, to speak to him about the likelihood that they would reach any town or settlement this day, when Alrend rose and cried out —

“She wakes! Highness, she’s awake!”

They gathered swiftly, like a small flock of birds, but hovered back to let the princess be the one to crouch beside Fidelity — who had propped herself up from her makeshift bed, plainly not just awake but alert.

Her veil was now as ragged as everything else in their company, trailing strands and threads that left her face mostly exposed. They had left it in place out of respect even as they tried to tend to her these last few days. But as Alsbet bent, Fidelity lifted the veil fully, threw it back, her eyes meeting the princess’s without any mediation for the first time.

“Highness,” she said, clearly, strongly. “will you release me?”

“Release you? Sister, you have been six days unconscious, you are not a prisoner …

Fidelity shook her head. “I don’t mean that I’m a prisoner, I mean … when I took my first vows they said only the emperor could release me from them. But a princess must have the right too, there is no emperor now, is there, and anyway you are, you were his daughter. And I never took my final vows — please, highness, I beg you to release me. The angels have chosen this path for me. I need to be released.”

From her half-sitting position she tried awkwardly to bow her head. Alsbet glanced at the men around her: Alrend had averted his eyes from the sister’s face, as though she had stripped before him, while Aeden was looking at her especially intently, as though recognizing someone whose name he knew but couldn’t quite remember.

“Highness, I need …”

Alsbet’s voice came out more harshly than she meant it. “I am princess of nothing, but in the empire of nothing where I rule, you are released from every vow and you may serve me freely or depart. Now let us help you rise, Fidelity, and see to your health —”

The sister, or former sister, pushed herself up and stood. The others gave her space as she pulled back her hood completely, exposing the hair that was starting to grow in, black around her tonsure.

She looked around at all of them — the soldiers’ faces, the old woman, the Brethons and the Narsils, the prince, Aeden, Alsbet.

“Not Fidelity,” she said. “Rowenna. Rowenna of — of nowhere, same as all of you.”

The victorious Falconguard had set up camp around Dernbridge, where Aengiss accepted the surrender of what remained of Varelis bar Veruna’s army. The Old Hound’s body and the corpses of Berenek Skorshi and Dethferd Rendell were decapitated, and the heads were sent back to Rendale for display. Save for a handful of legionnaires who had fled up one of the gold roads, the rest of the army was made prisoner, Mulias bar Sedura’s men included, awaiting whatever decisions Padrec made. A company was dispatched north to Caldmark, to offer terms of surrender to any Veruna loyalists remaining there, and birds were sent in advance of their progress in the hopes of making the surrender swift and certain.

Padrec reached Dernbridge at dusk on the day of the battle, and there, surrounded by his soldiers and with the scraping of gravediggers’ shovels making a ghastly background noise, the lords of the empire renewed their oath of allegiance to the House of Montair and the crown. It was a custom usually reserved for the coronation, but it seemed appropriate here — appropriate and effective, judging from the sour faces that Jonthen Cathelstan and Eldred Gerdwell wore as they mouthed the time-honored words.

The lords of the empire were sent back to Rendale the next morning, trading places with the women and children of Dernbridge, who had spent a relatively comfortable two nights under the supervision of the Castle chamberlain. But Padrec remained with the army all that day and into the next, resisting the urge to ride north himself, waiting for word from the pursuit of his sister.

He had to wait until close to midday on the third day after the battle, when Paulus bar Merula and five bloodied, bedraggled soldiers stumbled into the Falconguard's camp, with the news that Princess Alsbet and Prince Maibhygon had made good their escape.